By Roxby Hartley, Ph.D., Climate Risk Director, Business Development, EcoEngineers

Global Warming Potential over 100 years (GWP100) is masking the urgency of super pollutant mitigation. A temporal mismatch between how we measure greenhouse gases and when their damage occurs is a problem for climate action. Super pollutants, gases that deliver intense warming in years or decades rather than centuries, are systematically undervalued by our standard metric, GWP100. GWP100 serves as the foundation for virtually all carbon accounting. It is causing a serious underestimation of the climate impacts of super pollutants, which are accelerating the cascading feedback we are starting to experience.

What Exactly is a Super Pollutant?

Super pollutants are greenhouse gases with an outsized warming impact. While carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapor absorb infrared radiation at specific wavelengths, they leave spectral windows where heat can still escape to space. Super pollutants absorb precisely at these wavelengths, effectively closing these atmospheric escape routes and trapping heat that would otherwise radiate away.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) Sixth Assessment Report provides widely accepted values for GWP100: CO2 equals 1, methane ranges from 27.9 (fossil sources) to 29.8 (non-fossil sources), and refrigerants like HFC-134a have a GWP100 of 1,530. This metric answers the question: How much warming does one tonne of gas cause over a century compared to CO2?

Super pollutants typically deliver this heat input with accelerated timelines. Methane persists for just 12 years but creates 82.5 times more warming than CO2 over 20 years (GWP20). The century-long averaging reduces the warming to 30 times, with just 12 years of intense warming followed by 88 years after the methane has long been converted into CO2. Black carbon operates on even shorter timescales—days to weeks—delivering intense warming during its brief atmospheric lifetime, though standardized GWP values remain highly uncertain due to its complex atmospheric interactions. HFCs present different dynamics. HFC-32, for example, has significantly higher warming impact in the near term than its 100-year average suggests. Every kilogram released delivers front-loaded warming as we approach and pass climate tipping points.

Timing Matters

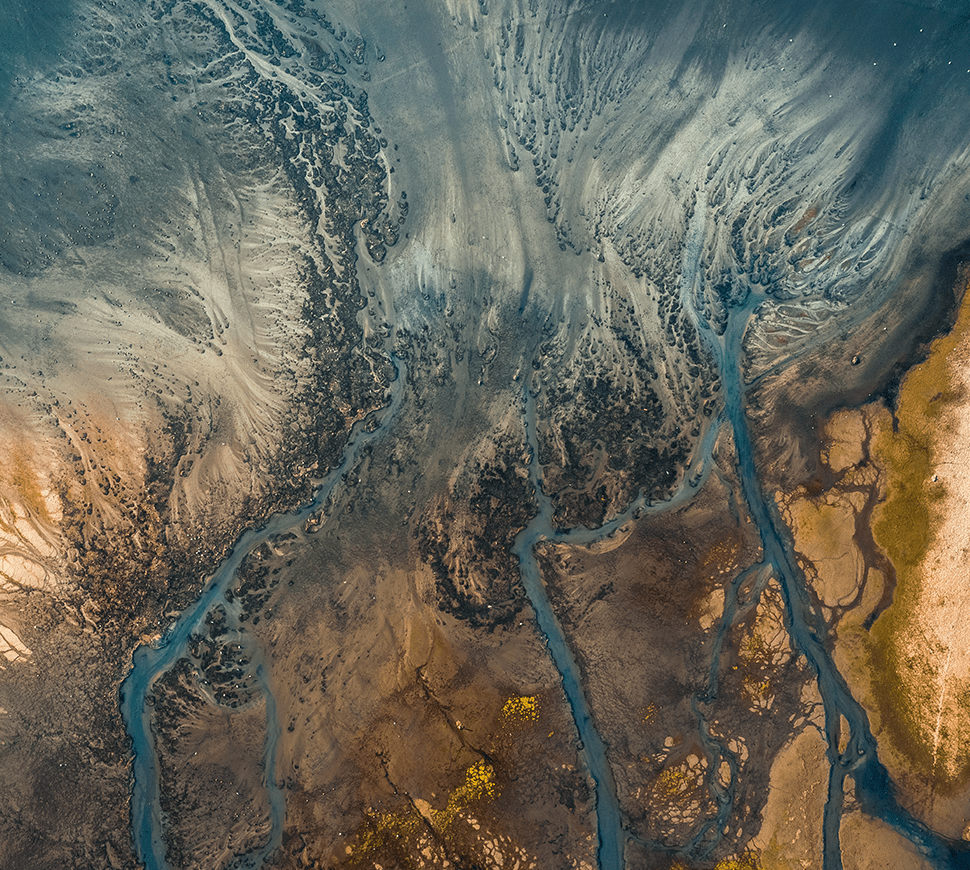

While the immediate radiative forcing can be correctly averaged over 100 years, it ignores the cascading impacts of heating the planet now. We do not know when we will reach tipping points in the Earth’s climate. Some have likely already passed. We do know the Arctic is losing albedo as highly reflective sea ice is replaced with dark ocean (Arctic amplification). The impact of melting all that ice over 12 years instead of 100 years adds a lot of extra energy to the Earth’s system, which, according to GWP100, is heavily discounted. It cannot be emphasized enough: Early warming triggers earlier feedback.

Why do we use 100 years for averaging heating? The choice emerged from policy convenience. Policymakers needed a single metric to compare gases with vastly different lifetimes—CO2 persists for centuries, methane for 12 years, some for months. A century seems like a reasonable compromise. The Kyoto Protocol enshrined GWP100, carbon markets, national inventories, and corporate reporting. What seemed like a good choice in 1997 may now have dire consequences.

What are the Impacts of Using GWP100?

This temporal mismatch drives systematic underinvestment and misunderstanding of how the Earth’s climate is responding. The business implications are compound. Companies using GWP100 for net-zero strategies unknowingly backload their climate impact—investment decisions favoring long-term CO2 removal over immediate super pollutant reduction miss far more cost-effective near-term wins.

What Can We Do?

We should be using GWP20 as an initial step; one can have a hopeful expectation that the front-loading of methane leak abatement, the destruction of refrigerants, the prevention of black carbon release, and forestry management will be prioritized by the increased economic gains.

Ideally, we would switch from tonnes of CO2 to focusing on what really matters: reducing the heating of the Earth. A direct energy crediting system is likely to be more helpful in evaluating real project impacts, allowing for the crediting of nascent albedo-increasing projects, and slowing the headlong rush into a much hotter world.

About the Expert

Dr. Roxby Hartley specializes in integrating biodiesel and renewable diesel into regulatory markets. With over a decade of experience in low-carbon diesel substitutes, he ensures client compliance across regulatory standards like the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) and LCFS. Dr. Hartley applies scientific expertise to drive innovative solutions for industry growth, with extensive knowledge in biomass and low-carbon fuels. He has acquired extensive acumen in the energy and oil industry and managed operations at a California biodiesel plant.

For more information about EcoEngineers’ services and capabilities, contact:

Roxby Hartley, Ph.D., Climate Risk Director, Business Development | rhartley@ecoengineers.us