The following is an article originally published July 4, 2024, by Biomass Magazine.

Advancements and Opportunities in Codigestion for RNG Projects

By David Lindenmuth, EcoEngineers

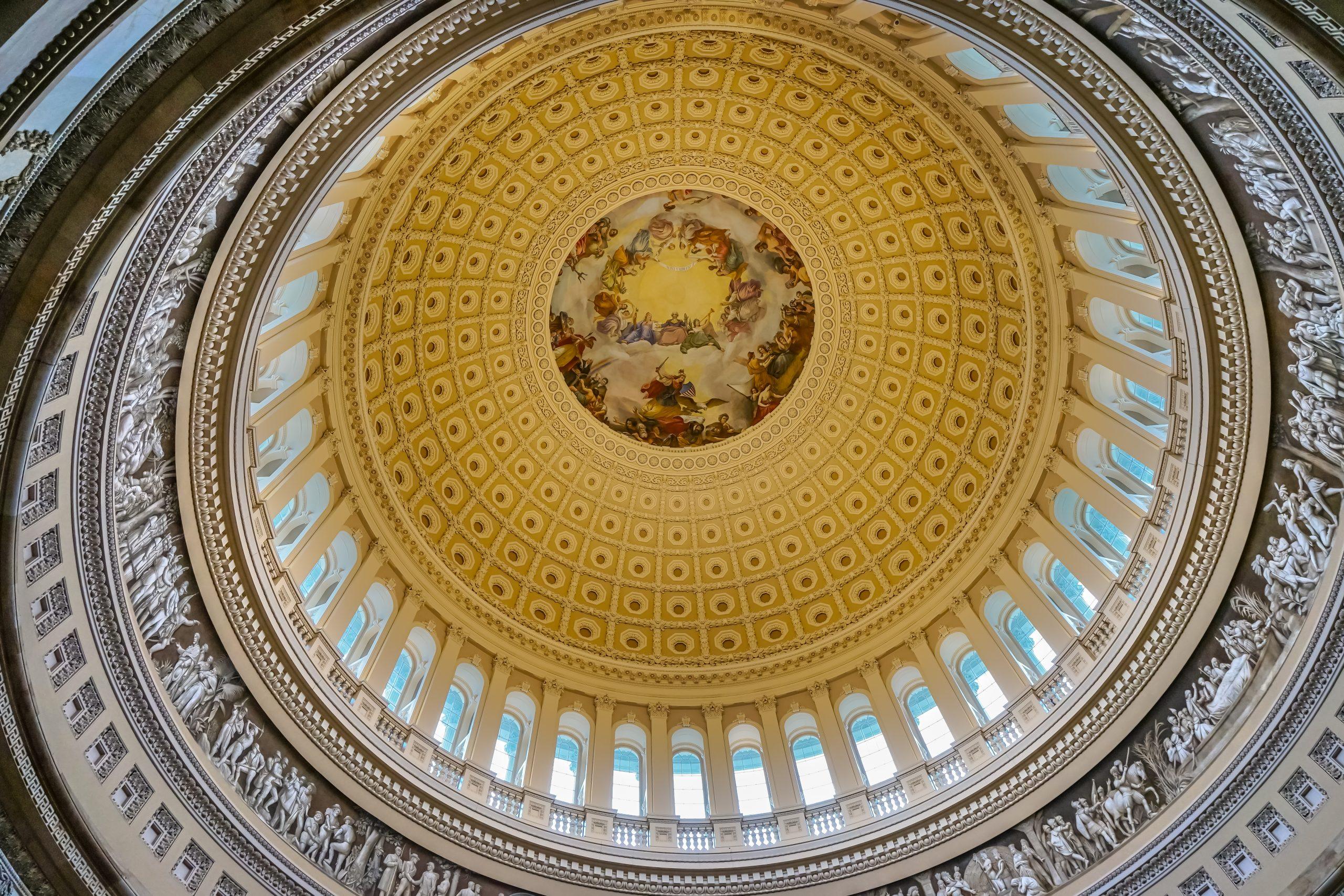

The arena of renewable natural gas (RNG) has experienced a pivotal evolution due to the recent regulatory advancements by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. A notable development is the expansion of the practical implementation of the regulation to allow codigestion with improved economic outcomes. The introduction of the new set rule signifies a strategic shift in the EPA’s approach to codigested feedstocks for RNG production, particularly impacting the financial justification and operational design of these types of RNG projects.

Codigestion and the New Set Rule

Codigestion refers to the process in which multiple organic feedstocks, such as dairy manure (classified as a D3 feedstock under the Renewable Fuel Standard) and food waste (classified as a D5 feedstock), are processed together in a single anaerobic digester to produce biogas. The EPA’s revised regulations have introduced methodologies that now enable the differentiation of biogas output derived from each feedstock type, thereby allowing the generation of both D3 and D5 renewable identification numbers (RINs).

Under the prior regulations, codigestion of D3 and D5 feedstocks resulted exclusively in the generation of D5 RINs. This limitation often negatively impacted the economic feasibility of projects due to the lower value of D5 RINs compared to D3 RINs. The revised rule, however, allows for the allocation of D3 and D5 RINs based on the “converted fraction,” a calculated measure of the amount of biogas produced from a D3 feedstock. This fraction is critical, as it determines how much of the generated gas can be attributed to each feedstock type, thereby unlocking the potential for higher revenue streams through D3 RIN generation.

Determining the Converted Fraction

Project operators now have the following two options for establishing the converted fraction when registering their facility with the EPA.

User-defined approach: This method requires operators to conduct precise measurements of their digester’s operating conditions, including temperature, pressure and residence time. The resulting converted fraction is applicable only if the digester operates within these measured parameters.

EPA predetermined values: The EPA has established four preset converted fractions for common feedstocks such as swine, bovine, chicken manure and municipal biosolids. These values are linked to specific operational conditions, such as a minimum temperature of 95 degrees Fahrenheit and hydraulic and solids retention time exceeding 20 days.

Project Considerations and Financial Implications

With the updated regulations, the operational setup and sizing of RNG facilities take on heightened importance. Facilities may want to be equipped to handle additional organic waste streams and ensure that their biogas upgrading systems can accommodate the increased biogas production. Furthermore, compliance with the new rule necessitates meticulous data gathering and management to satisfy the EPA’s requirements for both the user-defined and predetermined converted fraction methodologies.

The economic landscape for some RNG projects has been transformed by the new rule. Projects that were once limited to the D5 RIN market can now leverage the higher value of D3 RINs, potentially doubling annual revenue without an increase in biogas production. This financial uplift could drive the expansion of existing projects and the development of new ones. Additionally, the inclusion of D5 feedstocks, which often come with a tipping fee, presents a new revenue avenue for project operators.

Quality Assurance and Compliance

Ensuring compliance with the RFS’s RNG program requirements is critical to accessing the financial benefits of RIN credits. This involves a comprehensive quality assurance program that includes biannual site visits, ongoing data review, and adherence to mass and energy balance standards. For mixed digesters, additional verification layers are required, especially for the biogas energy calculation that establishes the D3 to D5 RIN generation ratio.

Future Outlook

The EPA’s registration timeline indicates that new project applications could be submitted starting April 1, 2024, with approvals commencing on July 1. All projects must align with the biogas reform rule by January 1, 2025, with a deadline of October 1, 2024, for updating existing pathways.

The revised EPA regulations herald a new era for mixed-waste digester RNG projects, particularly in the realm of codigestion. By offering a more nuanced approach to RIN generation and enabling more accurate financial modeling, these regulations have created fertile ground for innovation and investment in the RNG sector. As the industry continues to adapt to these changes, the focus remains on compliance, technical proficiency and leveraging the newfound opportunities to drive sustainable energy solutions forward.

Author: David Lindenmuth

Managing Director, RNG Services

EcoEngineers

dlindenmuth@ecoengineers.us

For more information about the EcoEngineers and the services we offer, contact us at

For more information about the EcoEngineers and the services we offer, contact us at

For more information:

For more information: